British Academy Mid-Career Fellow 2013-14, Dr Seán McLoughlin, who is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Philosophy, Religion and the History of Science at the University of Leeds, reflects on his research on Hajj-going from Britain for the extremely successful British Museum exhibition:

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam (2012). See also http://arts.leeds.ac.uk/crp/current-research/hajj/.

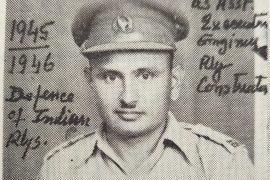

It was a great privilege for me to contribute in a small way to the British Museum’s exhibition, Hajj: journey to the heart of Islam. One of the final exhibition panels describes how my research team and I collected interviews with around 40 British Muslims concerning their experiences of the great pilgrimage. It also includes the picture above which captures me in conversation with a British Indian Hajji from Bolton. His account became emblematic for me of changing patterns of Hajj-going across the generations.

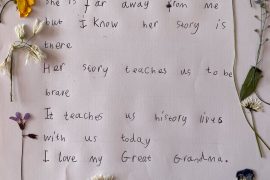

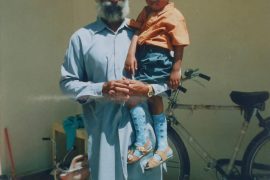

Mr Mogradia recalled how as a child in Bombay during the 1960s he had watched his father depart by ship for Jeddah on a 21 day journey, as well as telling how they then went together for Hajj by air 30 years later. While his father had reflected that perhaps a longer journey gave pilgrims more opportunity to prepare themselves spiritually for the Hajj, making his own first visit to the Holy Places Mr Mogradia’s own lasting impression was simply that:

I should have gone a bit earlier because the benefit I’ve got from the Hajj is to keep on the right path.

Such sentiments underline a theme very much apparent in my research: amongst the 25,000 or so British Muslims who go for Hajj each year, the average age of pilgrims is becoming younger.

Until recent decades, making the Hajj was not a realistic expectation for the vast majority of Muslims in the Islamic world, while even today those who make the journey are still often middle-aged or elderly. However, living in the West, British Muslims are a relatively wealthy community in global terms, and being a small national contingent they are not restricted in terms of Saudi Ministry of Hajj quotas. Of course, the overwhelmingly youthful character of the British Muslim population is also a driving force, as too is the current salience of religious identity for many.

A UK Hajj operator I interviewed in Lancashire confirmed this trend, relating how in 2011, 60-70% of his 395 pilgrims had been young couples in their 20s. An online survey of British Muslim experiences of Hajj that I conducted in 2011-12 is also revealing – https://www.survey.leeds.ac.uk/hajj. Among 205 respondents to date, mainly somewhat religious British Muslims in their 20s, 30s and 40s, only 35% of their grandparents had been for Hajj. In contrast, 91% of respondents had always expected to make the pilgrimage in their lifetime (even if they were sometimes surprised at how early that opportunity had come).

Perhaps not surprisingly, 78% suggested that it was best to go for Hajj as a young adult, and while many stressed the simple need to be physically fit to complete the testing rituals, like Mr Mogradia, just as many cited the opportunity to make or sustain a positive spiritual change early in life:

People have a misunderstanding that you should go older when you will hopefully be able to maintain a religious/spiritual change post-hajj, but this assumes that you will live that long. Besides, if hajj is going to cause positive religious change, wouldn’t be better to go earlier? Allah knows best, but there are traditions (Prophetic ahadith) strongly supporting going for hajj as soon as you are able financially and physically.

Dr McLoughlin’s research was funded by an Arts and Humanities Research Council award to the British Museum for its Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam exhibition (2012). He acknowledges the work of research assistants, Rabiha Hannan, Dr Muzamil Khan, Dr Asma Mustafa and Dr Jasjit Singh.

Picture courtesy of the Council of British Hajjis

Comments are closed.