In 1990, just a year before his early death aged 56, my father published his first book. He was a man who migrated to Britain in his youth with a limited knowledge of English and spent years working relentlessly to put food on the table, support a large family back in Bangladesh and pay our school fees.

We attended private schools, even though my parents had to struggle to put the fees together.

Scoring such a milestone as to publish a book was a monumental achievement. Thirty years later in 2021 his son, me that is, has just published his first book too and weirdly enough at the same age.

In their own ways. these books chronicle experiences across one hundred years of one family’s migrant history. My father’s book, Wage Earners: Working for a Better Bangladesh, offers a practical guide for how to make it easier for Bangladeshis living and working in Britain to send money back home to build businesses and support families. It was prescient, since remittances soon emerged as one of Bangladesh’s largest foreign currency earners, a pillar on which a once “basket case” economy (according to Henry Kissinger) emerged to become one of the world’s fastest growing. In the early chapters, my father describes the origins of Bangladeshi migration to Britain, by a generation before him where a small number of Sylheti merchant sailors settled in Glasgow in the 1920s. My book, Border Crossings: My Journey as a Western Muslim offers a prism into my story by connecting the experience of my father’s generation to what might be in store for my children too.

This knowledge is important for future generations because understanding what our parents dealt with helps us frame the context of our challenges and opportunities. We each have our specific reasons why knowledge of our heritage may help us. Three come to my mind in the instant that I write this blog:

- Understanding my parents’ and other elders’ attitudes to life helps me glean lessons which I can apply to how to deal better with mine. For example, my parents were disciplined in spending due to years of poverty as migrants, and today this helps my family appreciate the value of conserving resources even though our economic circumstances are vastly different.

- Recognising what my parents taught me helps me understand why I attach more importance to some matters and less to others. For example, my parents placed a lot of emphasis on knowing the wider family, and today this helps me value being a connected member of a big family network which I support, and which supports me.

- Thinking about what my parents didn’t teach me, due to limitations on their outlook or experience, helps me identify some of my own blackspots and weaknesses. For example, my parents only knew so much about how to guide us in dealing with the challenges of growing up in Britain, and today this helps me take a more receptive approach to trying to understand what my children might be experiencing as they grow up in Australia.

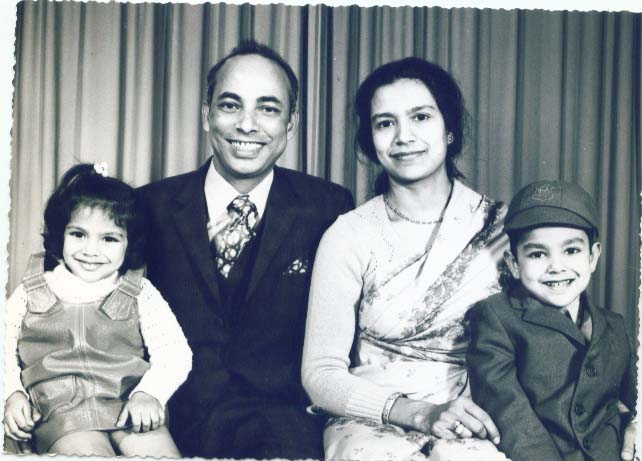

My father in Islington, c1959, a new immigrant with no assets.

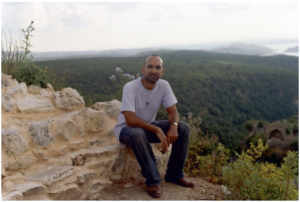

Me travelling and writing in the Levant, this taken near Qalah Salahdin, Syria, 2005

My son Zaki and I, Melbourne, just before COVID-19 hit us in 2020

Our migrant history doesn’t precisely follow the stereotype of “poor immigrant – no English or education – works hard – educates children – transforms next generation fortunes,” but borrows parts of it. Migrant stories are each unique. Part of the value of chronicling them is to appreciate that what migrants have been through is special, and that migrants are not a monolithic block of people, but humans with as diverse a narrative as indigenous people’s stories are as well.

My father used to give driving lessons to his friends (this is his younger brother) in his Ford Anglia

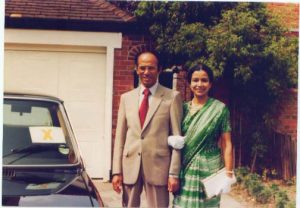

My mother was an elegant dresser, and despite being fluent in English and working much of her career, she always wore a sari.

An outing to Virginia Water, Surrey with my uncle visiting from Japan.

An outing to Virginia Water, Surrey with my uncle visiting from Japan.

Building an appreciation of our heritage helps us interpret the purpose and context of our lives and equips future generations with lessons of what’s gone before. Recognising our heritage doesn’t need to be a rose-tinted glorification of our past, but it can be the iron that sharpens our resolve to attain the promise of our future.

Mohammad Chowdhury is an author and management consultant based in Melbourne, Australia, and grew up in southeast London. His book Border Crossings: My Journey as a Western Muslim is available in bookstores across Britain as well as online (Unbound, 2021; ISBN: 1783529695, 9781783529698). His father’s book Wage Earners: Working for a Better Bangladesh is out of print, but copies can be requested from his son.

Author: Mohammad Chowdhury

Comments are closed.