Originally published on August 15th, 2022 on the Mayor of London website.

On a sweltering evening on Friday, the 12th of August 2022, a hundred and forty guests packed into City Hall, which hosted its first-ever event about the Partition of India. The historic event was curated and hosted by Sadiya Ahmed, Founder of the Everyday Muslim Heritage and Archive Initiative, as part of the Mayor of London’s Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm and its London Unseen programme.

A moving and provocative evening of discussion, art and reflection followed, we watched films of first-hand testimony, learned how Project Dastaan connected people to places and communities they thought they had lost using virtual reality, heard fierce demands for Partition to be a core part of British history education and reflected on what a memorial to Partition might look like.

Choosing City Hall as a venue for an event about the Partition of India had a bittersweet irony as City Hall is a government building which stands in a place steeped in the history of the British Empire. It stands on the banks of Royal Victoria Dock, a place of trade interactions of the East India Company, which not only traded but even came to rule large parts of India from the 1600s. And that of the lascars, the South Asian seamen. The often-ill-treated lascars sailed on ships bringing spices, tea, cloth and even opium from India to docks across ports in Britain.

The event hosted powerful and visceral discussions on the human impact of Partition on communities across generations in the sub-continent and Britain from panels reflecting academics, literary and community voices. Establishing a memorial to commemorate the impact of Partition was a central theme throughout the event; attendees could contribute ideas by writing or drawing their suggestions as an interactive activity. Many suggested moving away from traditional statues or physical constructs and considering parks, gardens, and other sustainable alternatives.

Whilst throughout the discussions, memorialisation was raised, and different perspectives were communicated. There was also the sentiment that whilst the broader community may favour a memorial, many felt strongly that a formal acknowledgement and apology for Empire and the mismanagement and lack of compassionate consideration around the physical act of Partition was far more warranted.

Another subject that attendees and panellists repeatedly proposed was the inclusion of Empire and Partition in the National Curriculum.

As the event curator and host, it allowed me to platform the subject of Partition and Empire from a personal perspective. One that would foreground the feelings and emotions of inter-generational transmission of stories and trauma. Together with providing a space where we could reflect on and collectively choose how we remember and learn from the memories and experiences of those who survived the events of 1947.

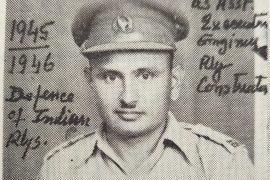

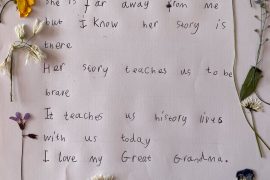

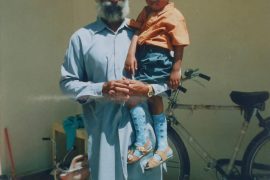

Alongside the discussions, an art and video installation curated by Khizra and Nidah Ahmed – (my daughter’s) visually detailed their late grandfather’s heart-wrenching and poignant Partition story.

On the 14th and 15th of August, some of us will celebrate, and others will commemorate the 75th anniversary of India’s independence from British rule, the creation of Pakistan, and a few decades later, Bangladesh in 1971.

However, Partition did not happen over a few days in August 1947. In truth, it was more of a legacy of an Empire’s policy of divide and rule, the hostile rhetoric instigated by the British presence to encourage the rise of Hindu and Muslim nationalism. It sowed the seeds of discord between friends, families, and neighbours. It caused mutual distrust and unrest between Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims, leading to killings and the separation of families and friends on the lines of religion and nationalism.

These divisions did not end with the Partition of India. Many have felt and suppressed the repercussions of a sudden and extremely violent partition for many decades. And are now beginning to be renewed as those who witnessed it are finding the courage to tell their stories so that future generations do not forget the human stories of a political event.

Recently, the media have begun to explore Partition from the human perspective in documentaries by the BBC and Channel 4. Films such as Bassam Tariq’s and Riz Ahmed’s Moghul Mowgli and, more recently, Hollywood’s Miss Marvel series convey the story of Partition from the perspective of the people who lived through it and of those who survived it. These interpretations bring this once hidden history to entirely new audiences from the older and younger generations’ points of view.

For many, it is the first time they are hearing about it, and others are expressing their surprise that these events happened so recently. And for some, it has a greater significance as it is a realisation that their grandparents or great-grandparents had witnessed the horror. Some will never know their ancestral story but are now aware they have a connection. And others who are not from a South Asian background are beginning to understand the implications of British colonialism from a different perspective.

Partition for me as a South Asian born in London to parents who migrated from Pakistan and Kenya is a profoundly personal subject. Partition not only marked the end of the British Empire in India, but it was also the reason for our forefathers’ migration to countries far and wide.

Empire and Partition are not histories of the past but a living history that embodies our connection to physical places, languages, food, faith, nationality, and a sense of belonging and home. Therefore, its legacy is complex and cannot be defined as a single experience or memory. For those of us who have migrated even as second, third or fourth generations, it can cause a sense of never really belonging, never really feeling accepted or safe, which is challenging to understand and reconcile when that place is the place, we call home.

We must not let the impact and ramifications of Empire and Partition on the South Asian community in Britain to be reduced to mere platitudes around milestone anniversaries. Therefore, the Everyday Muslim Heritage and Archive Initiative will continue working with academics, historians, and the South Asian community about Empire and Partition in identifying ways in which we can educate, commemorate, unite, and ultimately begin the journey to healing.

Speech delivered by Everyday Muslim Founder, Sadiya Ahmed.

Comments are closed.