“Iqbal Jafferee Sir, is this the house?”

“Is this the Geoffrey Street you wanted me to find?”

These were two messages I sent to Iqbal Geoffrey in September, that remained forever in unread on WhatsApp. It was the outcome of piecing together a scatter gun of clues, advice, and steers on locating a particular house from his time in London. When I finally pieced together the puzzle – was this a joke? Part of a life history that sat within an infinite universe of speculative fictions, absurd realities, and profound intrigue. But here it was – the clues led to a house adjacent to a road in Camden called ‘Geoffrey Street’.

I never received a message back, and in the following month I was informed of the passing of the late great Syed Muhammed Jawaid Iqbal, an artist, a lawyer, master prankster, a person who as Quddus Mirza noted, led a multitude of lives in his single lifetime. When I was told of his passing, my heart wept. إِنَّا ِلِلَّٰهِ وَإِنَّا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعُونَ. Iqbal Jafree, Sir – as I addressed him, returned to his Lord on 1 September 2021. I felt the loss of a guide, of a mentor, of a friend, of an uncle and of an artist whose presence in British art history gave me anchors of hope and perseverance. Anchors in relation to the consistent disappointment in art world cultures, a by-product when existing outside of the dominant cultures of white-Christian infused modernity-for-money curatese. Hope and perseverance to disrupt, to antagonise, to laugh and to dream beyond that disappointment.

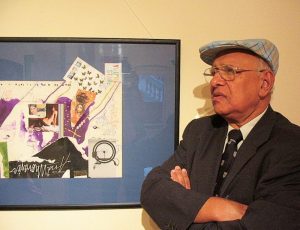

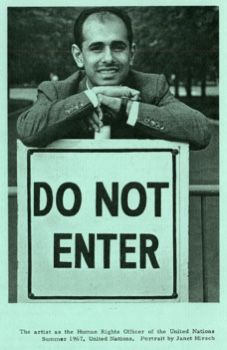

The Iqbal Geoffrey Sir that I know was born in 1939. He was born Chiniot, Pakistan. He was a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W) himself! By the age of 19 he had already been called to the bar in Pakistan, he had the mind of legal prodigy. Aged 21, he travelled to London, as an artist, calling himself Iqbal Geoffrey. A meteoric embrace – mingling with the elites of British aristocratic, political and art crowds. He meets Queen Elizabeth who tells praises him as an artist for Britain, he meets former Prime Minister Winston Churchill who tells him he should switch from painting to poetry. His painting ‘Epitaph 1958’ is acquired by the Tate in 1962. Despite this, he struggles after a flash of acceptance and is pushed to the fringe as an artist. Disillusioned by racist exclusion of the art world he posts an advert in the The Times, listing all his remarkable achievements and qualifications to date and highlighting, that despite all of this, he must live on the dole. Leaving London, he heads to Harvard Law School – which begins a blurry but blistering few decades as a lawyer, educator, accountant, husband, father, and artist – across America, Britain and Pakistan. He holds professorships in numerous institutions. At one point he the assistant district attorney of Illinois and holds intermittent exhibitions, at times included in group shows like ‘The Other Story’. He launches multiple lawsuits – against galleries, political entities and even the royal family itself. He sends 786 letters proposing legal action to Britain’s royal family in attempts of restitution for the Koh -e-Noor. He filed legal challenges to the Hayward Gallery and MOMA on the grounds of racial discrimination in their value systems of art. As a human rights lawyer, he was on an anti-corruption crusade. In his retirement, his crusade still burned bright through endless letters and emails, recycled and new, sent across the vectors of injustice he saw – whilst returning to making artwork in a prolific way – through endless collages from his Lahore home.

I first came across the name Iqbal Geoffrey when working at Tate in 2016. I often would browse the collection, search engine database, finding work that moved me. I came across a work, ‘Epitaph 1958’, with the artist associated being Iqbal Geoffrey. Both the artwork and artist page were blank in 2016 was blank. Empty. No description, information or insight beyond its tombstone data. I was intrigued, particularly by the fact that this artist had a Muslim name and that the work was acquired in 1962. This is rare. This is an anomaly. Tate’s canonised collections only started collecting work from non-European and American artists in a coherent way from the 90’s. Any artists or artworks from outside Euro-American nexus are complete anomalies. These anomalies often become prisoners in the collection, with no research or contextualisation given to them – they don’t fit the current collector curator culture of alleviating white guilt by making amends of exclusion through combing through history to see what was historically excluded for acquisitions and exhibitions. These are works already in the collections, bizarre marks on the white canvas.

I noted his name in my memory. Perhaps one day I’d research and find out who this is, and why the pages in Tate’s database are completely blank? But ever-disappointed of art spaces, my focus went away and his name stayed a memory in my mind. In 2018, I was working with Everyday Muslim, on their trailblazing archival project that saw the development of the Shah Jahan archive – documents, oral histories and records to sit within the library of the Shah Jahan Mosque, the first documented purpose built mosque in Britain. Supporting the archivist in cataloguing ephemera in the library, I picked up a copy of the Islamic Review from 1963. The Islamic Review was a journal published by the Woking Mosque Mission, a figurehead English language Islamicate journal that had a reach across the globe, printed between 1913 and 1967. I flicked through the pages, and suddenly saw the familiar name, Iqbal Geoffrey. Here was a an interview with a young Iqbal Geoffrey, a profile on this acclaimed artist, lauded in the art scene in London and with visions to become a historically recognised artist.

I noted his name in my memory. Perhaps one day I’d research and find out who this is, and why the pages in Tate’s database are completely blank? But ever-disappointed of art spaces, my focus went away and his name stayed a memory in my mind. In 2018, I was working with Everyday Muslim, on their trailblazing archival project that saw the development of the Shah Jahan archive – documents, oral histories and records to sit within the library of the Shah Jahan Mosque, the first documented purpose built mosque in Britain. Supporting the archivist in cataloguing ephemera in the library, I picked up a copy of the Islamic Review from 1963. The Islamic Review was a journal published by the Woking Mosque Mission, a figurehead English language Islamicate journal that had a reach across the globe, printed between 1913 and 1967. I flicked through the pages, and suddenly saw the familiar name, Iqbal Geoffrey. Here was a an interview with a young Iqbal Geoffrey, a profile on this acclaimed artist, lauded in the art scene in London and with visions to become a historically recognised artist.

This was a moment where I thought to myself, how is it that a public institution with a global reputation of being the official custodians of British Art history, Tate, had no information, insight or context around this artist in their own collection? And here I was, in a mosque library in Woking, being gifted an insight and context into the artist. A fitting way to find Geoffrey. Over the next few months, I started finding his trail of art and activism left through a bewildering tornado of bureaucratic complaint, institutional praise, and self-styled life stories – in archives across continents – in between art history, legal documents, and newspapers. One day, I received a WhatsApp voice note. It was Iqbal Geoffrey. The man, myth, the enigma himself. We began a correspondence that lasted the next few years – letters, voice notes, phone calls, emails, forwarded greeting icons on Whatsapp. A non-linear correspondence with constant shifts of focus – but I always knew what Iqbal Sir was telling me. I saw Iqbal Sir as a mentor, as a guide in tickling/tackling the dominant culture of the art elite through work, practice, and sheer existence. In language and performance. In Islam and in Arts. I think Iqbal Geoffrey Sir was the first, and still only person to tell me his what he feels our Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W) position on the contemporary elite art world would be – on curatorial and creativity in this space.

A monumental life. A monumental set of lives. A life story of an artist that has taken charge in embracing the fragmented, in rebellion and relation to an art history that is rigorous in clear categorisations and linear time. Iqbal Sir will forever haunt the underbelly of ‘pussycat curators’ and ‘kkknighthood cultures’ that have held art in the realm of injustice, in the realm of no love, in the realm of white supremacy.

A monumental life. A monumental set of lives. A life story of an artist that has taken charge in embracing the fragmented, in rebellion and relation to an art history that is rigorous in clear categorisations and linear time. Iqbal Sir will forever haunt the underbelly of ‘pussycat curators’ and ‘kkknighthood cultures’ that have held art in the realm of injustice, in the realm of no love, in the realm of white supremacy.

‘Agitate till they Vegetate. Then, that is art’ – Iqbal Geoffrey, Third Text 8 & 9, 1989.

Author: Hassan Vawda

Comments are closed.